By Caitlin Kelly

Some of you are already writing non-fiction, memoir, journalism, essays.

Some of you would like to!

Some of you would like to find newer, larger, better-paying outlets for your work.

Some of you would like to publish for the first time.

Maybe you’d like to write a non-fiction book, but where to start?

I can help.

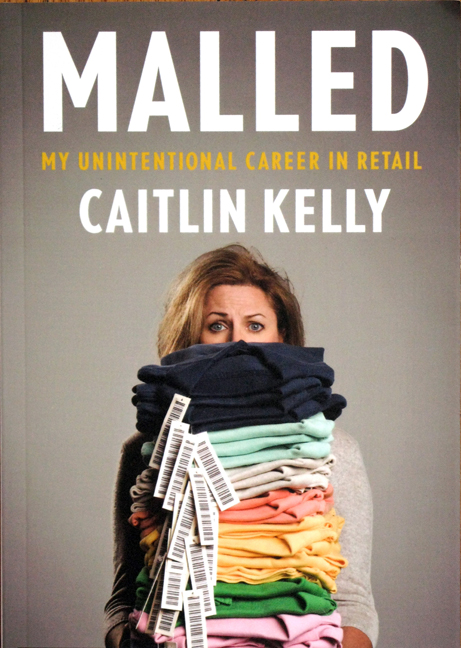

As the author of two well-reviewed works of nationally reported non-fiction, Blown Away: American Women and Guns and Malled: My Unintentional Career in Retail, winner of a Canadian National Magazine award and five fellowships, I bring decades of experience as a writer for the most demanding editors. I’ve been writing freelance for The New York Times since 1990 and for others like More, Glamour, Smithsonian and Readers Digest.

My website is here.

I’ve taught writing at Pace University, Pratt Institute, New York University, Concordia University and the Hudson Valley Writers Center — and have individually coached many writers, from New Zealand, Singapore and Australia to England and Germany.

My students’ work has been published in The New York Times, The Guardian, Cosmopolitan.com and others.

Here’s one of them, a young female cyclist traveling the world collecting stories of climate change.

On Saturday October 17, and Sunday October 18, I’m holding a one-day writing workshop, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. at my home in Tarrytown New York, a town named one of the U.S’s 10 prettiest.

It’s easily accessible from Grand Central Station, a 38 minute train ride north of Manhattan on Metro-North Railroad, (round trip ticket, $20.50), plus a five-minute $5 cab ride to my home — we have an elevator so there’s no issue with mobility or access.

Coming by car? Tarrytown is right at the Tappan Zee bridge, easy to reach from New Jersey, Connecticut and upstate.

Each workshop is practical, tips-filled, down-to-earth and allows plenty of time for your individual questions. The price includes lunch and non-alcoholic beverages.

$200.00; payable in advance via PayPal only.

Space is limited to only nine students. Sign up soon!

Freelance Boot Camp — October 16

What you’ll learn:

- How to come up with salable, timely story ideas

- How to decide the best outlets for your ideas: radio, digital, print, magazines (trade or consumer), newspapers, foreign press

- How to pitch effectively

- Setting fees and negotiating

- When to accept a lower fee — or work without payment

Writing and Selling a Work of Non-Fiction — October 17

What you’ll learn:

- Where to find ideas for a salable book

- The question of timing

- What’s a platform? Why you need one and how to develop it

- The power of voice

- Why a book proposal is essential and what it takes

- Finding an agent

- Writing, revising, promoting a published book

Questions or concerns? Email me soon at learntowritebetter@gmailcom.

You’ll find testimonials about my teaching here, as well as details on my individual coaching, (via phone or Skype), and webinars, (by phone or Skype), offered one-on-one at your convenience.

Want to register now?

Terrific!

Email me at learntowritebetter@gmail.com and I’ll send you an invoice and share travel details.