Written by a documentary film-maker, daughter of the late, great NYT journalist David Carr

By Caitlin Kelly

It’s ironic — we each have more access now, thanks to the Internet, to thousands of media sources from across the globe than ever before.

Yet I see such tremendous ignorance of what journalism is.

What we do. Why we do it. What we earn. Our many constraints and challenges.

So, as we close out this decade, this is my stake in the ground, a sort of Media 101. (If this is all overly familiar, sorry!)

Where does a “news” story come from?

The textbook definition of news means it’s new (something we haven’t seen or heard before); it affects the outlet’s audience (whether local, regional, national or global); it affects someone wealthy or powerful (a sad metric, but often used); it marks a significant change from prior experience; a natural disaster; a major crime.

It also, ideally, covers all levels of government. Ideally, also we cover major issues like income inequality/poverty, health, education, environment, etc.

Do journalists pay their sources?

No. This is common in some British tabloids, but not in North America, where it’s taboo. It demands cooperation from sources, yes, but it means (ideally!) that money doesn’t buy access or coverage.

Do sources pay to be in a story?

No! There is now the absurd belief — based on “journalism” like Forbes’ blogs — that you just pay to play. I’ve been offered payment many times by sources to write about them. Unscrupulous journalists accept, creating the fantasy this is normal. It is not.

How do I know who or what to trust?

This is now a huge and troubling issue — I recently attended a powerful and sobering event at the New York HQ for Reuters, with terrific panelists addressing this very question.

The first speaker, who flew in from London, showed the audience five videos and asked us to vote on whether they were fake or real. Some were fake, and so carefully created it was really difficult to tell.

In an era of such deceptive deepfakes, question carefully!

Who writes the headlines?

Not the reporters! Every outlet has a series of editors above the reporters and they will oversee the headlines and write them. No reporter writes their own headlines; freelancers can and do suggest one when pitching, and some will be kept.

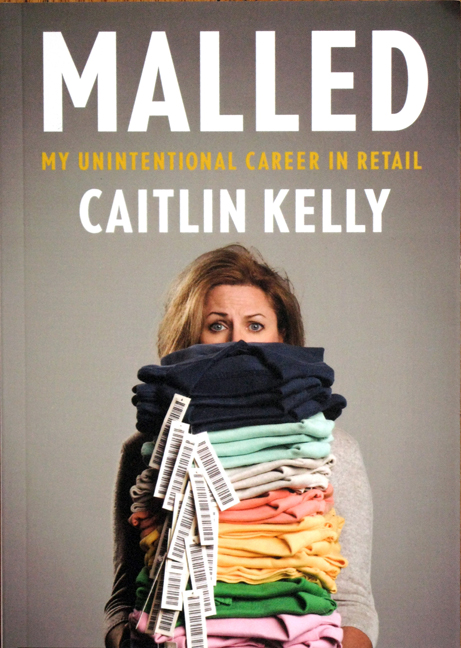

Same for book titles; I named my first book and my editor (thankfully!) named my second.

Who writes the captions for photos?

Editors. Sometimes the photographer.

How much do reporters make?

Hah! So much less than people imagine. In 2019, the American average was $40,081. To put this into context, I earned $45,000 as a reporter for the Montreal Gazette — in the 1980s. If you’re fortunate enough to get hired by a major national outlet, like Reuters wire service or The New York Times, you might get $90,000 or more.

How much do TV reporters make?

A lot more, depending if regional or national. Those working at the national level — sometimes more experienced and skilled — will make more. Locally, $56,455.

How much do authors make?

Some, millions. Some, pennies!

There are many, many tiers of book publishing, from academic houses to small indies to the mega’s like Simon & Schuster or Harper Collins, able to offer enormous advances to those they think worth the investment — like Michelle and Barack Obama, who got (reportedly) $65 million.

An “advance” may be divided into three or four parts: one on signing the deal, one on acceptance of the manuscript; one on publication and one (!) a year or more after publication. Hardly “advance”!

Every payment will likely lose 15 percent off the top to the agent who sold it.

Every book sold means more money, right?

Nope.

If your advance is $100,000, you must “earn out” that sum before getting another dime from the publisher.

And the game is rigged, since every book sold does not give the author the cover price!

We get eight percent of the retail price.

So this belief that a TV or radio or podcast appearance means a huge boost to our income from our books is wishful fantasy.

What exactly do TV and radio producers do?

There are “bookers” and producers who find and pre-interview people they think will be good on-air. You may have noticed a predominance of white men. People with no discernible accent.

How do people actually end up getting interviewed by the media?

A variety of ways. Some have in-house communications departments or PIOs (public information officers) to handle requests formally. Some have a public relations firm pumping out press releases all the time! Some know a journalist or producer personally.

If it’s a major news event, like a shooting or natural disaster, we speak to as many people there as possible — traumatic for them, often.

How do you get access to documents?

Some use a Freedom of Information Act — FOIA — to get at them. It’s been in American law since 1967, the legal right to access any document from any federal agency.

Sometimes we get them offered to us by an internal whistle-blower.

How are freelance writers paid?

Bizarrely, by the word. Sometimes a flat fee. These range from $150 to $10,000 or more. No rules. No guidelines. It’s every-man-for-himself. So a story of 500 words at .50 cents per word will pay less than a magazine piece at $2/word for 3,000 words.

We are not paid until the story is accepted — and that can take months. It’s a huge problem.

Stories also get “killed” — not used and maybe not even paid for, maybe 25 percent of the original fee.

A glossary:

Hed

The headline.

Sub-hed

A sub-heading within the body of a story, often used to break up copy and keep the reader moving.

Pull-quote or call-out

A phrase or quote that’s memorable, meant to entice the reader into the story.

Dek

A brief description of the story.

Lede

The first sentence or paragraph. Crucial!

Kicker

The final sentence or paragraph. Crucial!

Graf

A paragraph.

The 5 W’s and H

Who, What, When, Where, Why and How….every story should answer these.

B-roll

Images to illustrate a TV story or video that aren’t the main event. Sometimes shot in advance.

Nut graf

High up in a story, the graf that explains why the story is even worth reading.

Explainer

A detailed story to explain a complicated issue.

Presser

A press conference.

On the record

Everything you say is now for permanent, public consumption. (Off the record means it’s not — but only if you preface your remarks with this phrase, not afterward.)